Osamu James Nakagawa

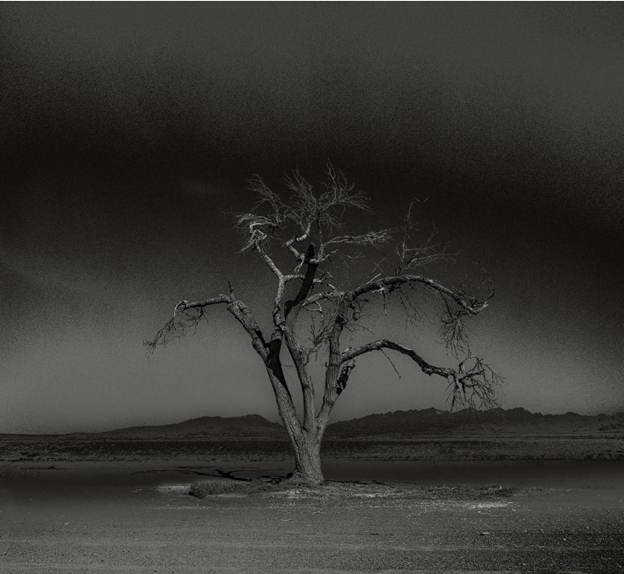

Poston 03, Arizona, Osamu James Nakagawa

“The turmoil of the pandemic, the killing of George Floyd, and the increased anti-Asian hate crimes during the Trump presidency were a painful reminder to me of America’s deeply engrained systematic racism. Amidst all this, as I turned 60, I had to part with my parent’s home in Japan. Together these things forced a personal reconning: I was symbolically severing my connection to the place my family has always called home, while questioning, yet again, my value in the eyes of my adopted country.

Am I American? Or Japanese? Japanese-American?

This has led me to wonder about the experiences of Japanese-Americans whose ancestors immigrated prior to World War II. Unlike my family, who came to the US during post-war economic boom, these older generation of immigrants and their descendants seemed guarded, as if they were carrying a burden of an American experience that was too much to speak of - a dark experience deeply rooted yet just under the surface, inherent in the structures of their adopted nation.

Two months after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour in 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, forcibly incarcerating approximately 125,000 Japanese and Japanese-Americans. mainly in camps in the arid American West. Many families suffered the dual trauma of losing their land, homes, and businesses while being isolated in the camps’ harsh desolate environments at the hand of their own government.

In 2022 I made a 15,200 mile pilgrimage to the sites where these camps had been, in an attempt to understand how the racism inherent in my American experience had carried a former generation of immigrants to places of such desolation. These trees emerged from the thousands of photographs I took of the sites. I felt them staring at me with the weight of their unspeakable memories. As I inhaled the light, air, dust, wind, and smells of the former camps, I took their portraits, connecting past and present, positive and negative, analog and digital to draw out their aura.

Now that I no longer have a home to return to, I have no other choice but to call this country my home.”

Nakagawa’s photography is heavily influenced by emotion and history which I felt when witnessing the physical prints. It wasn’t my experience but I still felt heavily burdened by the trials he has been through, feeling the weight of the world he feels on his shoulders. I could never understand what it feels like to be the subject of racial abuse like Nakagawa has experienced but the images perfectly display the burden he feels as well as the historical significance of these locations on Japanese-Americans.

The state of the trees is quite poetic and unnerving at the same time. It’s not clear which season specifically he shot these in during 2022 but we can hazard a guess at winter due to the bare branches and overcast skies. On the one hand it’s relaxing, in the sense that something has been able to grow and survive in a location that once brought such a horrible experience for so many people. The trees serve as a better memorial than any man made structure ever could and represent that life can continue despite previous hardship and has the ability to withstand current hardship.

On the other hand, the lack of anything else in the shot is cryptic and a clue that nothing else can thrive in such an environment. It implies that the past has held the location back so much that the environment is now irreparable. It could be seen as a warning rather than a monument of times affiliated with hatred and persecution in the 1940s are repeating themselves and humanity will remain in a similar state to the tree if we keep failing to learn from our mistakes. That’s certainly how Nakagawa described his experience with racism, drawing on modern examples that have tied him to a terrible point in history that is making him question his very identity. It’s a paradox that humanity simply fails (or refuses?) to learn from.