Experiencing A Radical Landscape at RAMM Exeter

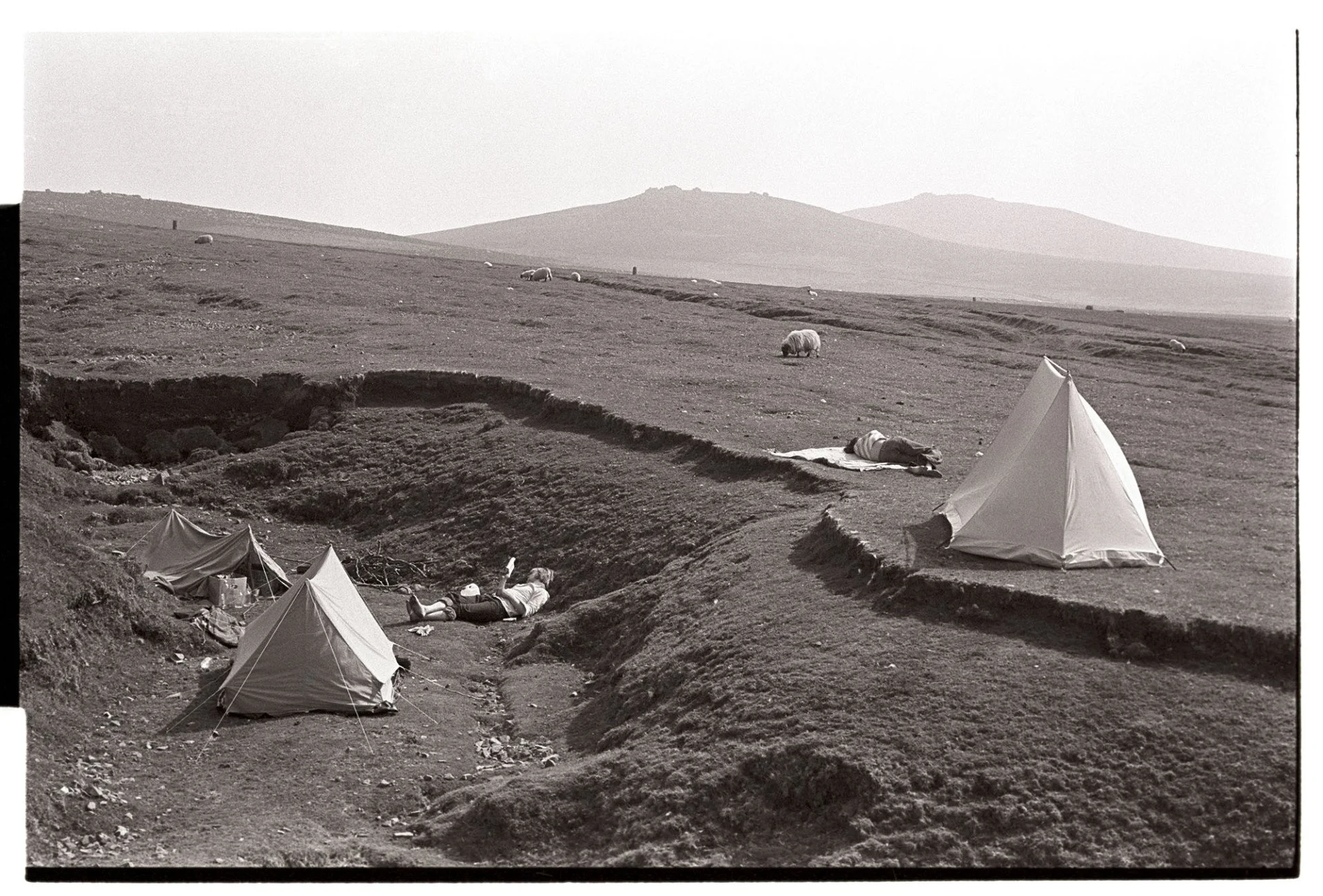

Near Oke Camp, James Ravilious. 1978

On 18th February 2025 I visited RAMM Exeter on a research trip to visit the photography exhibition Dartmoor: A Radical Landscape. The exhibition brought together photographic artwork from the late 1960s to the present day, inspired by the unique and evocative landscape of The Moors. With its open spaces, ancient woodland and layered traces of human activity, Dartmoor has long attracted artists, often depicting the landscape as a picturesque rural idyll. During the late 20th Century, artists began to explore radical new approaches, using Dartmoor as a space for experimentation: both a place for making and a source for creativity.

Dartmoor exists in the cultural imagination as a place of freedom and wilderness, but it is also a contested landscape and a microcosm of urgent issues facing Modern Britain. Concerns about the interconnected ecological crisis and climate breakdown, as well as who has access to the land, are explored by artists through collaborations with climate scientists, protestors, and other experts. This range of visually stunning and emotionally charged artworks offer new ways of appreciating and understanding Dartmoor’s special landscape and considering its future.

Listed below are a few highlights from the visit. This came at a crucial part of the project as I felt I was stagnating slightly. Sometimes it’s best to take a step back from the camera to take the opportunity to learn and self-educate.

1. James Ravilious

Moorland Scene with Fox Tracks in the Snow, James Ravilious. 1986

“I never set up photographs, preferring to take life as it comes. For pleasure and support I look at paintings more than photographs, though I particularly admire the work of Henry Cartier-Bresson, and the marvellous books of Olive Cook and Edwin Smith. Another inspiration is the work of the wood-engraver Thomas Bewick, undoubtedly the best record of English country life ever made.”

James Ravilious is closely associated with North Devon, where for 17 years he made a unique photographic record of rural life for the Beaford Archive, having moved to Dolton in 1972.

Although the majority of his photographs are of the ‘land of the two rivers’ between the Torridge and the Taw, Dartmoor frequently appears, often framing views towards the South West, from where North Devon gets much of its weather, and the Taw rises. Ravilious also made photographs of Dartmoor, where he seems to have enjoyed the freedom to focus on landscape.

The son of artists Eric Ravilious (1903-42) and Tirzah Garwood (1908-51), Ravilious trained as a painter and taught painting and drawing in London in the 1960s. He was inspired to take up photography after visiting the exhibition of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photographs at the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1969.

Ravilious loved photographing snow, with its opportunities for thinking in black and white and working with light and texture. The photograph Moorland Scene with Fox Tracks in the Snow was on Gidleigh Common when out with Chris Chapman. While the fresh animal prints suggest recent activity, the landscape also reveals evidence of centuries of human intervention: what appears to be a path or river is in fact a streaming channel created when the waters of the North Teign River were redirected for tin production.

2. Chris Chapman

Middlecott Farm, Chris Chapman. 1982

“I look at the sale ring at Chagford pony sale and wonder at the 4 hats. They’re all different… and they all slightly belong to different eras. You’ve got Colin Northmore with the bowler hat, the flat cap on another farmer and the flowerpot hat on Mr Andrews, who was a dealer. I love that.”

Chris Chapman took his first photos of Dartmoor in 1972 while studying at Torquay School of Art, before joining the new Documentary Photography course at Newport College run by Magnum photographer David Hurn.

In the Summer of 1974, Chapman embarked on a photographic walking journey over Dartmoor, with a donkey to carry his equipment. He moved to Dartmoor the following year, documenting rural life and customs in photography and film. He never intended to stay but writes the ‘Dartmoor always drew me home’. His photographs have been published and exhibited extensively and are in public collections including Arts Council and International Centre for Photography, New York. A permanent exhibition of Chapman’s Dartmoor Photographs is now installed at the Providence Methodist Church in Throwleigh.

3. Alex Hartley

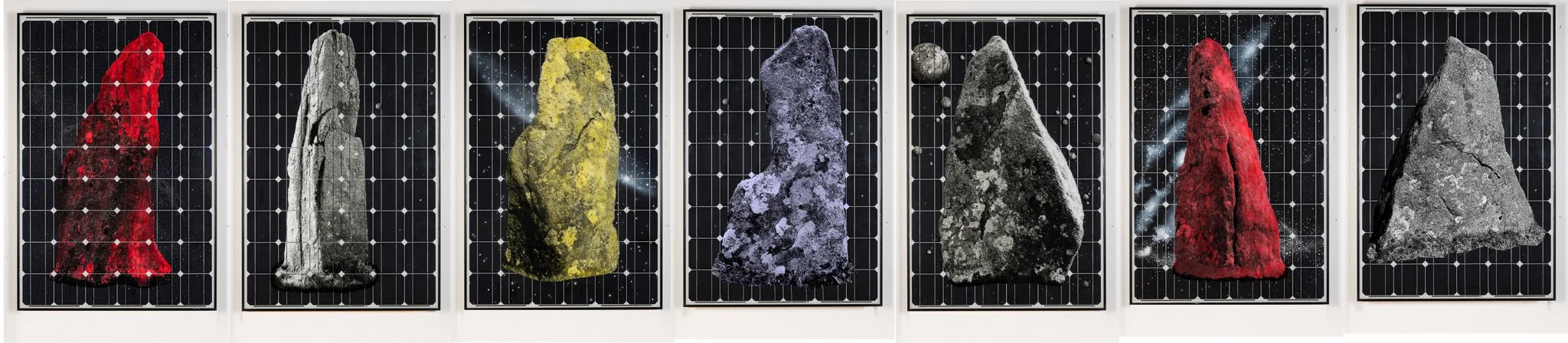

The Summoning Stones, Alex Hartley. 2024

“Neolithic stones have been here for 3000, 4000 years and they’re still visible. You can reach back through time and touch the very thing that these people touched. It’s so rare to find those places. And there’s something very specific about Dartmoor, about how iconic the rocky outcrops are. I can see it when I’m away from here and there’s not many places that I feel that way about, where they really follow me around and they are in me.”

Alex Hartley is based in East Devon and climbs on Dartmoor. His artwork explores ways of physically experiencing and thinking about our built and natural environments. Internationally renowned and critically acclaimed, his work has featured in exhibitions across the UK, Europe, USA and Japan, with his most recent solo exhibition part of the Architecture Venice Biennial in 2023. His practice often engages with the dual ecological and climate emergencies such as in the ground-breaking work Nowhereisland in 2015 which followed his discovery of a new island uncovered by a retreating glacier. Declaring it the world’s newest nation, he invited the public to become citizens and towed the island from the High Arctic to the South West coast.

The Summoning Stones is new work that has been realised through Alex Hartley’s research at the museum and in its stores where he searched for what he describes as ‘a resonant magic object’. He found that RAMM’s Kingsteignton figure, a 2000 year old wooden human figure on display on the ground floor, contained the same ‘vibrant energy’ that he detected in Dartmoor’s stone circles. He invited people to stand at the centre of this installation, ‘to basically be plugged into the main frame’ saying, ‘I want the energy of these rocks to transfer into the viewer. It’s almost certainly unachievable, but I really have that as the goal for it.’