Dystopia: A Long-Form Exploration of a Psychogeographic Land Art Practice on Dartmoor

Dissertation for Unit 702 of Masters Degree

Okehampton Danger Zone, Dystopia. 2025

The literal definition of a dystopia is ‘an imagined world or society in which people lead dehumanized, fearful lives’ (Webster, 2019). The aim of this project was to create a make-believe world on Dartmoor to convey the consequences of societal and mental breakdown by using walking, mapping, and documenting through photography as a form of narrative-building. The project served as a method of displaying the unravelling of the mind - more specifically, my mind. I have a chequered past with my mental health, struggling through melancholy and anxiety disorder so responding to this in a creative way and using the landscape to work through and process my emotional state was a key objective. I am also working with the landscape in this context as the project has developed into a documentary project of embodiment over a landscape photographic practice. I’m using the Dartmoor landscape to build the dystopia but haven’t specified this in the project description. The aim is to give my audience permission to enter the state of mind in this world through active engagement and interpret the narrative how they see fit. How this is interpreted will of course be different depending on each person’s circumstances in their personal lives and, if I can find a way for them to share their opinion of the work, this could make for an interesting insight into how my work impacts different people.

There is a connection between emotion and landscape as somatics are heavily influential when discussing a dystopia. My methodology naturally shifted to Land Artistry as a result but coming to this decision resulted in me critically re-evaluating what my actual goals for the project were. By the end of Unit 701 the project was a mess of irrelevant video content and physical embodiment with the inclusion of self-portraiture but without these failures I would not have been able to conclude that this wasn’t the correct direction to take.

fig 1. Robert Darch. (2018) The Moor. Photograph

My initial inspiration came from my personal experiences with anxiety disorder. I wanted a way to express myself and how I could only see the world as good or bad and nothing in-between. These themes led me to the conclusion of a long-form auto-ethnographic exploration as melancholy is a long-form illness and shooting everything in black and white demonstrates an awareness of how one in this position might see things as only one way or another. I was also inspired by photographer Robert Darch’s The Moor which ‘depicts a fictionalised future situated on the bleak moorland of Dartmoor’ (Boddington, 2018). In this photo book he similarly explores the idea of dystopia on Dartmoor so the initial struggle was finding a way to show this differently to him. I eventually concluded that I wanted my world to have a single inhabitant - the photographer. Darch’s work features portraits of people experiencing the world (fig.1) whereas I wanted the project to stand on its own emotionally without the queue of human presence. Darch says that “when the moor is cloaked in low cloud and fog the place feels otherworldly, apocalyptic and empty” (FotoRoom, 2019). This is reminiscent of the literary theory of pathetic fallacy where the weather impacts the narrative and emotion the subject feels. Dark, misty conditions are often associated with depression and dark overtones - something relatable in a dystopia.

fig 2: Matt Marshall. (2025) Dystopia. Photograph

The first Research Intensive I engaged with was Immersive Audio. Following the development of the project I opted against a video final output but the Intensive was beneficial because it taught me the importance that audio can have in relation to conveying emotion. I have taken this new found information and applied it to my Instagram correspondence of the project to ensure that the sound I select to accompany the post and text is relational to the dystopian narrative of struggle and hardship. An example of this is a post I made with the caption The Climb from a shoot at Yes Tor (fig 2) accompanied by the song Heaven in Hiding by Imminence. This combination works perfectly together to convey my story because the title of the song suggests that something good is hidden for the main character in the environment but something is preventing them from seeing it. The conditions are that something in these circumstances stops the viewer seeing the ‘heaven’ but this is how I can integrate audio moving forward with the project.

I also attended The Use of Colour Research Intensive run by Richard Webb. Admittedly, I selected this option due to a lack of choice from other Intensives and struggled with my mindset in the first session as my work featured black and white photography over colour. Despite the colour aspect not being relevant to my work, Webb was able to portray how we are in charge of our own narrative as the creator of the work and we can weave it however we deem fit. He demonstrated this through the story of Orpheus and how he attempted to rescue his lover but looked back on Hades and lost her forever. Webb used colour to change the story and find a more fitting end where he succeeds in his mission. It proved to me that we can create a story simply because we can and there doesn’t need to be a more complex description than that of curiosity.

How I represented the dystopian experience was something I needed to tread carefully around. There are people living in the real world who feel the rule they’re living under is close to the definition of a dystopia, which is why I haven’t specified an exact location where the narrative is set. Dartmoor is simply a tool to demonstrate the world that the wanderer inhabits and is not a place that exists in the narrative. Another ethical consideration was my respect for the environment and the rules that are implemented to protect historical sites, which there are a lot of on Dartmoor. A common theme in dystopian depictions are abandoned or deteriorating environments so avoiding physical interactions with these and not trespassing to unauthorised areas was my ethical stance on this front.

Dystopia has introduced me to a whole new way of working beyond just photography. I have began integrating a hybrid methodology into my project that reflects a connection between myself, the established presence in the world I’ve created (named the wanderer) and the Dartmoor landscape. Through embodying my character’s experience of interacting and navigating a dystopia I have developed my own method of mapping, connecting to the dystopia through words, and documenting the parts of the world I access through photography.

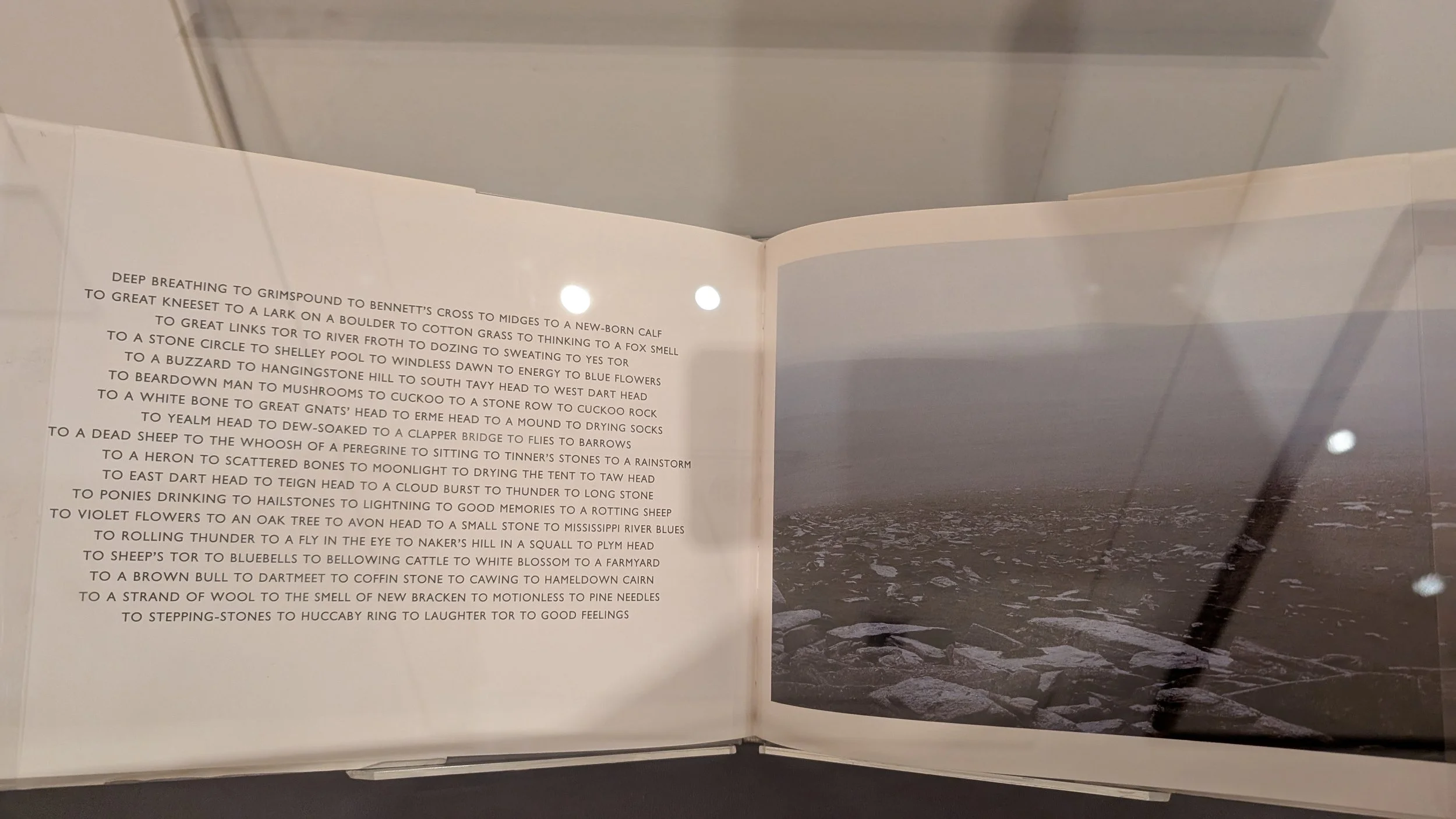

fig 3: Richard Long. (1972) Two Walks. Exhibit

The visit to the Dartmoor: A Radical Landscape exhibition was revolutionary for the project’s development. Seeing how multiple methodologies came together in an organised and collective way was inspiring and made me realise my work also had the potential to be the product of a hybrid methodology and I didn’t just have to limit myself to photography with this.

The project is informed by walking-based and psychogeographic practices (meaning how the world impacts emotion) with a heavy reference to the work of Richard Long’s Land Art. Long’s influence in selecting the path for my narrative was especially intriguing. His way of storytelling through his own perspective of the world helped me when deciding which location on Dartmoor would work with each part of the journey through my dystopia. His cross-methodology of Dartmoor based practice considered the emotional connection with a landscape and his photography documented his interaction with the environment, to the point where the act of walking was the actual artistic value and not his photography. In his Two Walks exhibit at the Dartmoor: A Radical Landscape exhibition (fig 3) he mixes photography and text to document how ‘walking can be a way of interacting with the world to gain a new awareness of our surroundings’ (Dartmoor: A Radical Landscape, n.d.). What this shows is Long becoming more than just the artist - he has also ‘become the marker’ and the documentation through text and photography is the means of showing how his act of walking breaks him free of the boundaries of the traditional notions of what art should look like. The art doesn’t need to be physically in front of us but evidence of the act through cross-methodology presentation can interpret the weight of artistic value to us as an audience.

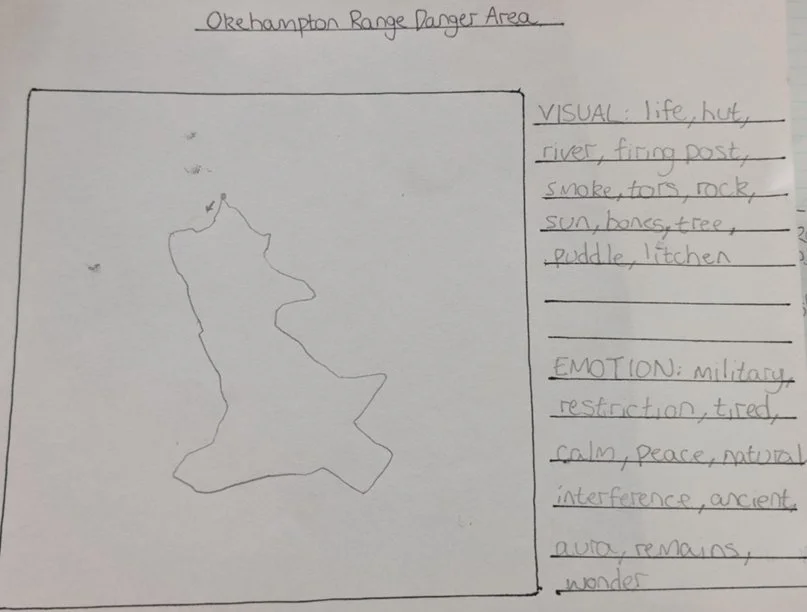

fig 4. Matt Marshall. (2025) Okehampton Range Danger Area. Mapping + Language

It is from the inspiration of seeing Long’s work that I opted to write some words down on location as I walked, inspired by Long’s small descriptions of his journeys (fig 4). I did this to document my emotion as the purpose of the photography is based on visual documentation so another medium had to be used as an expression of feeling. I also devised my own method of mapping that is loosely based on Long’s map work, the key difference being that Long’s mapping specifies Dartmoor as the subject area. My mapping is more ambiguous and shows just a drawn line as it’s based on a fictitious setting. The mapping, words and photography are yet to culminate into a clear direction in terms of project output. Long has found a way to integrate his methodologies so they mix successfully and it’s now about considering the way I’m going to collate them effectively which will provide the bulk of Unit 703.

The mapping aspect of the project has been heavily influenced by Tim Ingold. In his book Lines he speaks of artist Paul Klee who implies that the line of a map is ‘free to go where it will, for movement’s sake’ (Ingold, 2016, p.75) which suggests that the drawn line on a map can be fluid. Our notion of what a map looks like is sometimes based on the ‘gestural re-enactment’ (Ingold, 2016b, p.87) but physically drawing it whilst on location is surely based on how we move in a landscape rather than how we remember moving in a place? This is why I have gone down this route rather than drawing the maps after I have walked around parts of Dartmoor.

This is underpinned by themes of dystopian fiction. One such influence is militarisation, depicted in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale. This is the idea that a military presence keeps order in her dystopian world, and the population is forced into subjugation by The Guardians of the Faith. The protagonist Offred describes how ‘I don't go to the river anymore, or over bridges. Or on the subway, although there's a station right there. We're not allowed on, there are Guardians now…’ (Atwood, 1986, p.31) which suggests they aren’t allowed in certain areas due to military presence. Why is this the case though? The unspoken word of why they aren’t allowed there adds more depth to the narrative and I wanted to use these themes of the unknown to imply more to my audience about why the world ended up as it did.

fig 5. Nicholas J.R. White. (2013) Observation Post No.6. Exhibit

It’s the idea of militarisation that also led me to Nicholas J.R. White’s The Militarisation of Dartmoor, a photo book documenting the key points of interest in the Dartmoor landscape linked to military history. The objective of his project came ‘from a desire to visually explore Dartmoor, beyond just the picturesque scenery that one typically associated with a National Park’ (J.R. White, 2013). I felt like my project was missing context in the narrative, despite wanting people to reach their own conclusions on the meaning of the project. I liked how my images were emotive and reflective of the struggle of mental hardship but it was lacking evidence of the theme of conflict. White’s images contained grid references and showed Dartmoor’s militarisation in a unique format as none of his images contained soldiers training or live firing but rather implied that it was an area of conflict in a subtle way. He notices the observation posts of Dartmoor ‘make a concealed effort to blend into the surrounding landscape’ (J.R. White, 2013). White understands the significance this area has to military training but also understands why the military obscure their observation posts in the interest of the public, such as Observation Post No.6 (fig.5). Or is it for the greater good of the public?

I have allowed my practice to lead my research by getting on location and creating. I was aware that too much planning would lead to me becoming a researcher over a practitioner which was not the objective. I authorised myself to interact with the landscape I was basing myself in and, as a consequence, knew what to research in order to lead my project in the right direction. My research resulted in the conclusion of using a hybrid methodology as well as exploring militarised areas of Dartmoor to portray a landscape and mindset under siege.

I have hit creative challenges along the way but the main thing when this happened was to take a step back and shoot something completely different. I would usually do this by refreshing my studio practice so that I could brush up on my technical skills with artificial lighting that I’d gained the knowledge of on BA Commercial Photography. These one day intermissions enabled me to effortlessly reintegrate myself into Dystopia whilst still being involved in some form of photography to stay switched on.

To evaluate Unit 702 I would argue that I achieved my objectives. Given the fact that I wasn’t expecting refined outcomes and the main objective was for the photography aspect to have more direction and purpose to better establish my narrative of a dystopian landscape, I believe that this was successful. I also wanted to investigate different mediums of art that I could incorporate into the work beyond just photography which I’ve also succeeded in doing. The natural progression by the culmination of Unit 703 will be to have a clean, refined output as I am still in the process of figuring out the best way to present and collate my work but this will be a task to be completed by the very final deadline. I have the benefit of having a test space at Ocean Studios with staff, post-grad photography students and Commercial Photography students where I can gather opinions on if the presentation is suitable. One definite output will be a photobook but I’d like to get the work out into the public domain by more publications so a wider audience and opinion is gathered. I have already published the work through DOCU Magazine and I left it to them to order the 20 images I provided so that I can get a preliminary understanding of photo book ordering and process.

References

Atwood, M. (1986). The Handmaid’s Tale. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, p.31.

Boddington, R. (2018). Robert Darch’s series The Moor argues that we are already living in dystopia. [online] Itsnicethat.com. Available at: https://www.itsnicethat.com/articles/robert-darch-the-moor-publication-photography-071218

Dartmoor: A Radical Landscape. (n.d.). [online] p.13. Available at: https://rammuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2024-DART-GCUC.pdf. FotoRoom. (2019).

Robert Darch Constructs a Fictional Series Set in the English Moors. [online] Available at: https://fotoroom.co/the-moor-robert-darch/. Ingold, T. (2016a). Lines. Routledge, p.75 + 87.

J.R. White, N. (2013). The Militarisation of Dartmoor. Webster, M. (2019).

Definition of DYSTOPIAN. [online] Merriam-webster.com. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/dystopian.

List of Illustrations

fig 1: Darch, R. (2018) The Moor. [Photograph] Dartmoor National Park

fig 2: Marshall, M. (2025) Dystopia. [Photograph] Dartmoor National Park

fig 3: Long, R. (1972) Two Walks. [Exhibit] RAMM Exeter

fig 4: Marshall, M (2025) Dystopia [Mapping + Language] Dartmoor National Park

fig 5: J.R White, N (2013) Observation Post

No.6 [Exhibit] RAMM Museum Exeter

Bibliography

Atwood, M. (1985). Handmaid’s Tale. S.L.: Vintage Classics.

Bates, D. and David, P. (2017). The Prox Transmissions. Marvel Entertainment.

Clarke, G., Macfarlane, R. and Marshall, S. (2021). Unsettling landscapes. the Art of the eerie. Bristol: Sansom & Co.

Daniel-McElroy, S., Evans, P. and Dalton, A. (2002). Richard Long: A Moving World.

Dartmoor: A Radical Landscape. (2024). Available at: https://rammuseum.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/2024-DART-GCUC.pdf.

Hudson, M. (2022). ‘I’ve Drunk from Every River on Dartmoor’: Land Artist Richard Long on Changing the Face of Art. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/nov/15/ive-drunk-from-every-river-on-dartmoor-land artist-richard-long-on-changing-the-face-of-art.

Ingold, T. (2016). Lines. Routledge.

J. Salmon Limited (1999). Landscape of Dartmoor.

J.R. White, N. (2013). The Militarisation of Dartmoor.

J.R. White, N. (2016). Black Dots. Another Place Press.

Long, R. (2006). Dartmoor. Verlag De Buchhandlung Walter.

O’Leary, E. (2023). Dawoud Bey’s Somatic Landscapes. [online] Carla. Available at: https://contemporaryartreview.la/dawoud-beys-somatic-landscapes/.

Orton, J. and Worpole, K. (2013). The New English Landscape. London: Field Station, Cop.

Orwell, G. (1949). Nineteen Eighty-Four. London: Penguin Books.

RAMM. (2024). Dartmoor: A Radical Landscape. [online] Available at: https://rammuseum.org.uk/whats-on/dartmoor-a-radical-landscape/.

starsetonline (2025). STARSET - dark things (Official Music Video). [online] YouTube. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2AB3_l0iqSk.

Tillmans, W. (2014). On The Verge of Visibility.